It goes like this: conditions such as depression are caused by an imbalance of chemicals in the brain called neurotransmitters, and medication to correct this imbalance is the cure.

However, within the previous few years, doctors and researchers have theorized that mental illness is much more complicated than this–and that, perhaps, treatment through medication is not all a patient needs to be healthy.

Despite all the advancements in modern medicine, we still know surprisingly little about the human brain. It is so complex that, even when it comes to mental health treatments that have proven effective, scientists do not always understand the exact mechanisms at play.

Because medications that increase serotonin levels in the brain–called SSRIs, or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors–are often effective in the treatment of depression, many doctors simply assumed that low serotonin was responsible for a depressed patient’s symptoms. However, in recent years, research has found that other chemicals such as dopamine and norepinephrine also plays a role in mental health, and that all neurotransmitters behave in much more complex ways than previously understood.

But could non-biological, non-chemical factors influence mental health as well?

In 2014, the World Health Organization published a report titled “Social Determinants of Mental Health,” which investigated how various “social, economic, and environmental circumstances” influence mental wellness across various populations. The report found that individuals and communities disadvantaged by factors such as race, gender, or socioeconomic class were the most likely to suffer poor mental health.

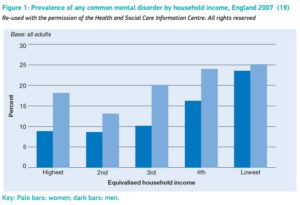

In England in 2007, researchers measured the rates of common mental illnesses, such as anxiety and depression, and how they correlated with gender and household income. Between men in the highest-earning 20% of the population and those in the lowest-earning 20%, there is almost a 15% increase in the prevalence of mental illness. Lower-income women were also more likely to experience mental illness than their higher-income counterparts, but that difference is closer to 7%–half of what it is for men.

So what does this mean? Income inequality cannot be measured in the chemical makeup of the brain, yet it appears to have a statistically significant impact on mental health.

Looking at these findings through a sociological lens–rather than a medical one–suggests a range of possibilities. Could it be that men are emotionally impacted more by poverty because of a cultural expectation to provide for their families? Since women’s rates of mental illness across income levels are more consistent, but much higher, perhaps financial inequality is not the main barrier to ending sexism? Maybe both? Or neither? Regardless of your conclusion, the existence of this sort of data calls into question the theory that mental health is governed by biological factors alone.

Not only do social inequalities lead to declining mental health, but they also impact who is able to seek out and receive quality care.

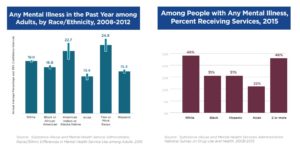

A 2017 report by the American Psychiatric Association found significant racial disparities between those who need mental health treatment and those who actually receive it. Among mentally ill adults in 2015, white Americans were 17% more likely to receive mental health services than black Americans, despite both races reporting similar rates of mental illness. The APA theorizes that this could be due in part to a lack of cultural diversity and understanding within the healthcare field–patients from minority populations may worry that their healthcare provider will not recognize or understand how experiences of discrimination impact their mental health.

What makes mental health is not just the absence of mental illness.

The WHO report defines mental health as “a state of well-being in which every individual realizes his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to her or his community.”

As you can see, this definition encompasses far more than can be measured chemically or treated medically.

In 2017, a representative for the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights issued a statement echoing many of the same conclusions reached by the WHO report.

“Biomedical interventions will remain as an important treatment option for severe depression and other mental health conditions. However, we should not accept that medications and other biomedical interventions be commonly used to address issues which are closely related to social problems. There is a need of a shift in investments in mental health, from focusing on ‘chemical imbalances’ to focusing on ‘power imbalances’ and inequalities.”

So how can we start working to improve mental health for everyone?

We now know that what makes up mental health is much larger than can be defined by the medical model alone. This means that our ideas of what constitutes healthcare and treatment for mental illness will need to expand as well. Improving mental health in our society will require action from all angles: from pushing for insurance coverage for non-pharmaceutical treatments to working to increase racial diversity and cultural sensitivity in the medical field.

There are no simple solutions for complex problems. But, if we as a society begin to address these underlying factors that impact mental health, the positive effects of our actions will be felt for generations to come.

Recent Comments